Veil-PowerView

I was led to PowerShell in the past few years as it began to rise to prominence in the information security community. As a penetration tester and red teamer for Veris Group’s Adaptive Threat division, my job depends on keeping abreast of current attack tools, tactics, techniques and procedures, and PowerShell is definitely the ‘new hotness’ in infosec. It’s been gaining traction ever since the seminal DefCon 18 talk PowerShell OMFG given by Dave Kennedy and Josh Kelly in 2010, and an increasing number of attack toolsets, public and private, have been ported to the language. To clarify, PowerShell does not help attackers actively exploit or compromise systems, but it does assist with the phase of the attack cycle we in the security community call post-exploitation. Once an attacker gains control of a machine, the availability of the PowerShell language provides an excellent environment to perform a variety of actions that can help turn that compromise of that single system into the compromise of an entire domain.

Matt Graeber‘s post “Why I Choose PowerShell as an Attack Platform“ articulates better than I could why PowerShell is great for post-exploitation. Essentially, Microsoft has given attackers a means to run fully-featured attacker toolsets (or malware) on any modern Windows operating system by providing a whitelisted, AV-safe environment with access to the full .NET Framework. Being able to dynamically load PowerShell scripts into memory without touching disk is an added plus, allowing us as attackers to leave as forensically small a footprint as possible on an exploited machine.

My contribution to the offensive PowerShell community, Veil-PowerView, is a component of the open source attack toolkit I co-founded called the Veil-Framework. The toolset started with Veil-Evasion, which generates AV-evading executables, branched into payload delivery with Veil-Catapult, and then moved into situational awareness with Veil-PowerView. As we began to move into more advanced engagements, we began to focus more on PowerShell as a post-exploitation tool; Veil-PowerView is the result of gap areas we encountered between our operational goals and the capabilities of current public tools.

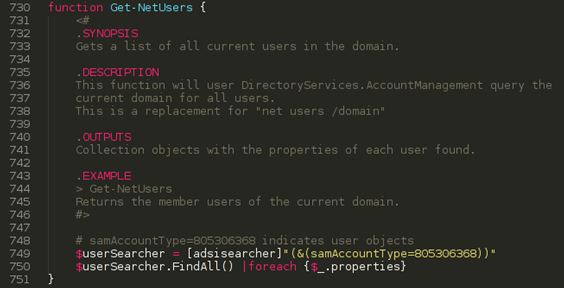

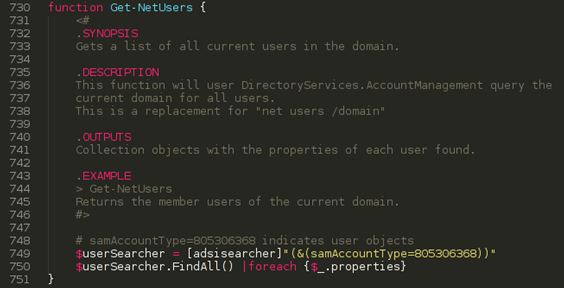

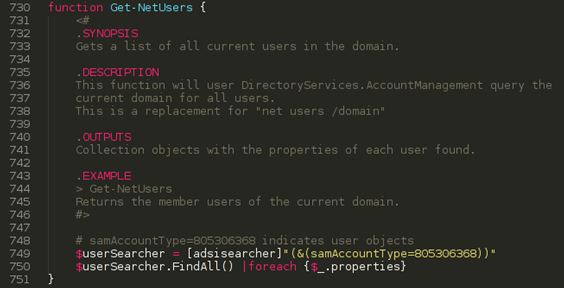

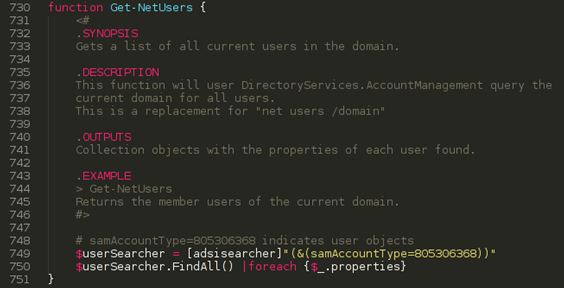

PowerView’s inspiration initially came from an experience on an assessment where a client had implemented an interesting defense- the disabling of all “net *” commands on domain machines. Initially this threw a wrench in some of our normal post-exploitation activities, however during our post assessment breakdown we started brainstorming ways around this particular defense in case we encountered it again. Bypassing it completely ended up being trivial through the use of PowerShell’s DirectoryServices.ActiveDirectory namespace and Active Directory Service Interfaces:

PowerView’s Get-Net* cmdlets now handle everything from retrieving the local domain/user, querying Active Directory for domain user and group information, to adding local or domain users and more:

This was the initial motivation for the tool, a contingency in case we encountered a situation again where net.exe was disabled. The next phase of development was inspired by Rob Fuller’s netview.exe project, which “utilizes various Windows API calls to perform enumeration across network machines“. PowerView’s port of netview.exe, Invoke-Netview, will query Active Directory for machines using ADSI, and then for each machine will enumerate sessions using a Win32-api implementation of NetSessionEnum, logged on users using a Win32-api implementation of NetWkstaUserEnum, and available shares using a Win32-api implementation of NetShareEnum. The Windows API calls were later rewritten using information from Matt Graeber’s post “Accessing the Windows API in PowerShell via internal .NET methods and reflection”. This allows PowerView to operate completely in memory, as it doesn’t rely on csc.exe to temporarily compile C# code in order to access the Windows API.

From there, a few related functions were built to hunt for users on a domain. Invoke-UserHunter will query Active Directory for users of a particular group, say “Domain Admins”, and then utilizes similar techniques as Invoke-Netview to enumerate loggedon users and users with active sessions, matching up where target users are located. Invoke-StealthUserHunter takes a more subtle, ‘red-teamy’ approach to hunting down user locations. It will then extract all servers found from user HomeDirectory entries, and run a Get-NetSessions call against each found file server to get current user sessions on those targets, again matching up where target users are located. Both of these functions are among the most useful for us on security engagements: once we find a way to access target machines, say through local admin password reuse, one of the things that used to be tedious was finding where high value users were logged in. With PowerView, we can now automate and accelerate this previously painful process:

From there, more and more functionality has been added into PowerView as gaps have arisen for us on assessments between what we want to accomplish and the functionality of current toolsets. PowerView can now query AD for machines likely vulnerable to common network exploits, find all available shares on the network readable by the current user, search for sensitive files on target file shares, enumerate local groups/users for some machines, and more. Check out PowerView’s README.md for a complete command listing, and Get-Help for flags and examples for almost all functions.

PowerShell is an extremely effective attack platform for offensive operations, and is an essential tool for penetration testers and red teamers alike. And we’ve just scratched the surface with current projects- as more attack toolsets are ported to the language we’ll begin to see what’s truly possible with PowerShell from an attacker perspective. There’s a lot the offensive and professional PowerShell communities can learn from each other, and hopefully a collaborative bridge can be built between our two groups.

Share on: